The following post was written by Gerry Levandoski, a AsiaTravel client who traveled with us on a small group journey with Yosemite in September 2010. This is the first of a series of articles he wrote detailing his experience. We begin in Jiuzhaigou…

———

Daybreak added disappointment to the dread Esther and I already felt. Cold and rain had returned, and the day’s itinerary had us hiking and overnight camping. Hiking has become a favorite activity. If I have the proper clothes, I don’t even mind walking in the rain. But I will always choose a hotel bed and pillows over a sleeping bag on an air pad.

Park visitors need special permission and local guides to enter the Zharu Valley, our destination. The park zone contains a monastery, a couple temples and stupas or shrine, plus Zha Yi Zha Ga (“King of All Mountains”), a 14716’ peak sacred to local Benbo Buddhists. The Benbo or Bön is an ancient pantheistic sect with shamanistic and animistic traditions. Bön predates Buddhism in Tibet, but today’s followers combine Bön and Buddhist beliefs and practices.

The valley is a biodiversity treasure house, too. According to the park website, the valley contains 40% of all plant species existing in the whole of China. By the time we boarded the van that would take us to the valley’s mouth, the air was trending warmer and the rain had slowed to a drizzle. The van left us at Re Xi Village and proceeded to the campsite with the equipment and supplies.

Re Xi reflects the changes wrought by the area’s conversion into a park. The houses feature recent and modern two-story, stone and tile construction. One old style three story home remains as a museum piece for the tourists. Of wood construction, both the interior and exterior exhibit colorfully painted religious symbols and images.

Tigers on the exterior discourage evil spirits. Inside, the kitchen and living room are one. This main living space features Tibetan-style lacquered wood shelves and panels. The family altar, with a lotus positioned Buddha, a cropped peacock feather array and an incense burner, occupies a prominent shelf. Multiple teakettles sit atop the central wood-burning stove, ever ready to accommodate guests. Yak butter tea, anyone?…Adjoining bedrooms, workrooms and storage occupy the main floor’s remaining interior space. The top story serves as a hayloft.

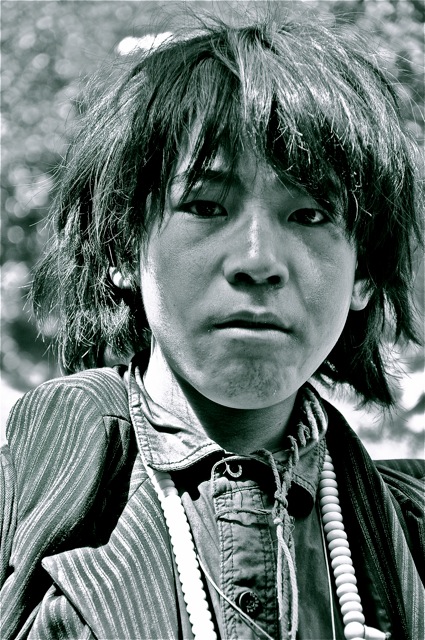

Today, the villagers continue to wear traditional clothing and earn a living in the tourist industry rather than relying on hunting and subsistence farming. The few remaining farm animals find shelter in detached buildings rather than the traditional ground floor stables.

We did not follow the van up the road. Instead we proceeded over an easy rolling trail on the river valley’s right wall, first, through a temperate forest, and then past abandoned fields, orchards and crumbling concrete and wood farm cottage remains. When we began hiking the group’s mood was subdued, but the weather continued to dry and to warm, which lifted our spirits. Soon, our conversation and laughter proscribed any chances of encountering the local fauna. Even the birds kept their distance. John and Jay, two park rangers, served as our guides/interpreters.

On my own, I watch the trail for wildflowers, fruiting bushes and unusually-shaped leaves, but I’m no botanist. John and Jay’s powers of observation and knowledge of the local flora astonished me. They stopped us repeatedly to point out a plant or shrub, give us the English name and to tell us its value in herbology or cooking. Many wildflowers were in bloom including some orchid varieties. Ramon, an avid nature photographer stood beside himself with delight:

After a three or four mile hike, we reached the campsite, a piney flat beside the river and a teal-watered reservoir. To our delight, the tents were already up. The site provided clean pit toilets WITH tissue, and a ranger cabin where we could relax at tables and chairs.

Phillip, our Tibetan guide, was already in the kitchen making dinner preparations.

John explained that the Chinese have yet catch on to camping as recreation, but the national parks service hoped to promote the activity. Park management had originally intended Zharu Valley to become a campground as well as a horseback riding area.

However, the local inhabitants objected vehemently because of the valley’s religious importance, so future usage now stood unclear. Our hosts had erected our tents next to an enclosure that once housed giant pandas. For better or worse, the bamboo inside the enclosure died, so the pandas were released.

We had stopped for lunch along the trail and dinner was still a couple hours away, so when John and Jay offered us another hike, the majority accepted. This trail took us deeper into the forest toward Zha Yi Zha Ga summit. We passed a Benbo stupa and a nearby field strewn with prayer flags. In case you don’t know, Buddhist prayer flags commonly come in five color combinations, blue, white, red, green and yellow. While sometimes displayed as long banners, most flags I’ve seen are roughly 8”x12” rectangles with a prayer, and often a symbol, printed upon them. The flags are sold sewn to a cord so they can be strung up where they will flap in the wind.

Buddhists believe in something like a universal consciousness rather than a god. The wind waving the flag means the prayer is being continuously recited. The best analogy might be votive candles lit beforea Catholic church side altar honoring Saint Somebody or the Virgin Mary. Just as the candle burns until used up, so the prayer flags remain until they disintegrate.

I find the concept beautiful, but the practice far less lyrical. One sees masses of thin, faded and tatted cloth drooping toward the ground or, having already landed, lying in the mud. Yet, maneuvering through this chaotic flag array triggered a long-lost childhood memory of summer days when my mom had the sheets and clothes from our eleven-member household hung out to dry in the backyard. This vision lacked poetry, but I recalled the simple joy of walking between the waving sheets wearing nothing but cutoffs. In the moment I felt again the sheets’ cool, damp touch on my hot bare skin.

The rain restarted as we moved further along the trail. We passed the roofless walls and doorless portal of a claustrophobia-inducing stacked stone shelter. John explained that the builders/inhabitants had had an opium poppy plantation out here. A tiger carried off one of their children. They abandoned the homestead only after the same tiger carried off their second child. Everyone grew quiet and began paying closer attention to the meadow grasses and wildflowers around us…

Esther voiced the obvious questions. “How long ago did this happen?” (In the 90s.) “Are there still tigers here?”

(Maybe—butprobably not)

“I want to see a tiger.”

A drizzly mist enfolded us on the return walk and the trail was muddier and colder for it. We trudged into the ranger cabin to find the dinner tables set and Western beers and California wines set out for sharing. During a recent trip to California and Yosemite, John purchased these treats anticipating our visit and this meal. Phillip, our chef du jour, created the best meal we ate in China. Fresh vegetables rescued from the primordial cooking oil ooze, and meats spared a deep fryer plunge. Generally, our Juizhaigou hosts treated us like the VIPs.

While we were chatting over cookies and tea, Don pulled a bottle of clear liquor and several thimble-sized shot glasses from his pack. His actions raised a collective “Ahhh” from his group, which caused the rest of us to pay more attention.

I happened to be sitting on Don’s right. He set a thimble before each of us and filled them with liquor. I raised the drink to my nose and detected a faint soy sauce fragrance.

“What is it?” I asked.

“Mao Tai.”

Don raised his glass, and indicated that I should do likewise. “Ganbei!” he shouted and downed the drink. Why not? I thought and followed suit. Mao Tai comes from fermented soygum, not soy beans. Its alcohol content varies between 35% and 53%. At the state dinner during Nixon’s 1972 China visit, Prime Minister Zhou En-Lai touched a match to his glass demonstrating to the President that Mao Tai can indeed catch fire. A young Dan Rather called it “liquid razor blades.”

Despite all that, I found the taste experience surprisingly smooth (At least that was true for the brand Don shared with us). Even notorious tea totaling Esther enjoyed a second glass. Mao Tai first gained a worldwide reputation after winning a gold medal at the 1915 San Francisco World’s Fair, but I’d never heard of it. If you drink hard liquor, the next time you go to a Chinese restaurant with a bar, try Mao Tai and form your own opinion.

With a great meal in our bellies and good spirits to warm us, we were set for a long evening of stories and jokes. Our hosts, however, found it impolite to clear the tables while their guests remained seated there. It was only about 9:00, but they had to clean up before going to sleep. Zhao Bei politely told us we had a long day of travel tomorrow, and we should go to bed.. We had a good laugh over this, but obeyed.

It wasn’t my best night’s sleep. The sleeping bags were cozy enough, but in the middle of the night, my air pad popped and I laid across the uneven contours beneath the tent the rest of the night.

Did I mention that I don’t like camping?

———

This year, this trip departs September 14, 2011. For inquiries, please click here: Hiking Yosemite Sister Parks in China or e-mail us at info@wildchina.com.

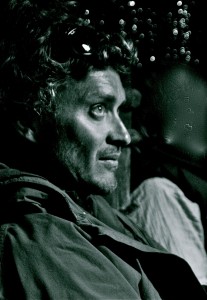

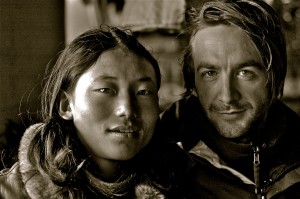

Image: Gerry Levandoski & Ramon Perez. See all photos on Facebook here.