Beautiful and diverse, southwestern China’s Yunnan province is not only one of our most popular destinations, it is where AsiaTravel was born. In the initial stages of China’s dizzyingly fast modernization, Yunnan avoided much of the environmental degradation experienced by other provinces. But little is known about the current state of Yunnan’s environment in the face of accelerating development.

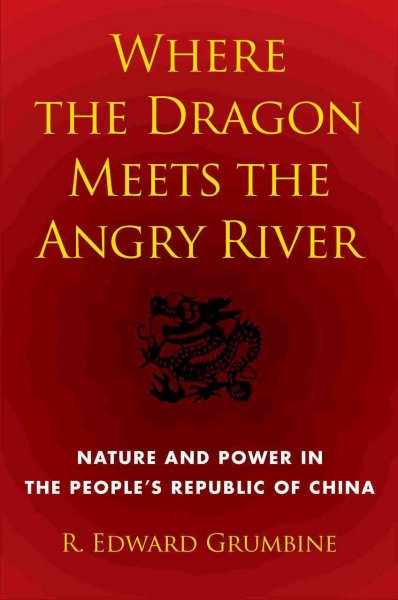

R. Edward Grumbine, Environmental Studies faculty at Prescott College, Arizona, is working as a senior scholar with the Chinese Academy of Sciences at the Kunming Institute of Botany.

Grumbine’s research focuses on the battle between development and conservation in Yunnan. His book on this subject, Where the Dragon Meets the Angry River, was published last year by Island Press.

Grumbine recently shared some of his experiences and views on Yunnan and more in this interview, reprinted here with permission:

How much time did you spend in Yunnan conducting your research for this book?

R. Edward Grumbine: From 2005, I spent around three to five weeks in Yunnan every year. I began to write upon my return to the US in 2008.

Where did you conduct your research in Yunnan?

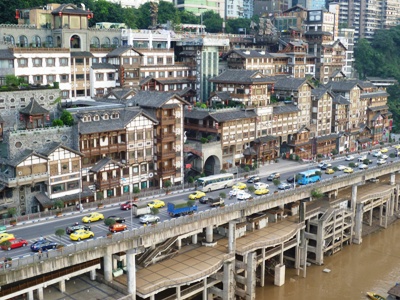

Grumbine: Between 2005 and 2010 I’ve hiked from the Nu River to the Lancang as well as areas around Zhongdian [Shangri-la], Deqin, Yubeng and Xishuangbanna near the border with Myanmar. I’ve also spent time in Pudacuo National Park, Laojunshan, Nizu, and in ‘Banna near the China-Laos border. Additionally, I’ve made it out to Gonggashan and Kangding in Sichuan province.

I’ve lived in Kunming since last August and will be here on a fellowship until 2012. Throughout my time coming to Yunnan, there have been numerous short trips to Beijing as well.

What led to you deciding to write a book about Yunnan?

Grumbine: The book is about Chinese conservation, using Yunnan as the main focus of the story. Imminent development of all kinds, but especially hydropower projects in the Nu Valley, helped me decide to write a book. I decided to write after my second trip to Yunnan in 2006, but I did not begin to write until 2008. I needed more time here to gain perspective on very complex issues.

What were some of the biggest surprises that you encountered in the course of your research?

No real surprises, but lots of interesting experiences. I guess the biggest surprise was the role of the local government versus the role of the central government.

What was surprising about that?

Grumbine: Most foreigners believe that the central government in China has 100 percent authority and complete control. After all, China is a one party-state system.

But the reality is that local governments at all levels have real power in terms of implementing Beijing’s laws, rules and regulations, so things are very complex on the ground. This situation does not match the stereotypes that many Americans and other foreigners have about power in the PRC.

Why is Yunnan’s biodiversity important?

Grumbine: There are three ways to answer this question.

Yunnan’s biodiversity is globally important as it is a true hotspot with more species than most other places on Earth. Yunnan is therefore important to the world if you value the existence of wild species and habitats.

Yunnan is regionally important from the standpoint of providing ecosystem services like clean water, good air, carbon sinks from intact forests, reduced soil erosion, and much more. Provision of these services depends on ecosystems continuing to function.

Species make up ecosystems; losing species impairs to X degree ecosystem health and function, depending on the details. So far, however, people are used to getting healthy ecosystems for free, even if Yunnan sits upstream from Southeast Asia.

Yunnan’s diversity is important to local people since they depend to a greater or lesser degree on nature for food, shelter and clean water. These local values change from place to place in Yunnan.

What makes Yunnan different from other biodiversity hotspots around the world?

Grumbine: One big difference: Yunnan is close to the most diverse temperate area anywhere on the planet!

Another difference is — there are still many local people who depend directly on natures’ services— the majority of humans living here still are rural, not urban. Of course, even Kunmingers depend on getting water supplies from somewhere.

Another difference— no one knows how much biodiversity has already been lost in Yunnan, especially large mammals and primates. The last surveys were done 15 to 20-plus years ago and are way out of date.

I expect that today virtually every primate and many if not most large mammals are either extirpated from Yunnan or much more endangered or threatened than we think. This is the “dirty secret” of biodiversity here.

The impacts of losing or reducing the populations of these animals have never been studied in Yunnan – or anywhere in China – but research in the US shows that ecosystems function less well when large critters are lost from the system, and that there is a time lag from species loss to negative effects appearing.

Given recent news out of Beijing suggesting that China plans to dam the Nujiang, what do you think the impact on the Nujiang and Salween valleys will be?

Grumbine: So far, nothing yet is confirmed about the dams going forward in the Nu, but I expect that some will indeed be built. Impacts will depend on how many total dams and which ones of the 13 proposed originally will get built. Not all the dams would have the same impact – some are worse than others.

Then you get into defining what a specific impact is – relocating how many local people? With or without adequate compensation? Where do they get moved to? What about the loss of a free-flowing wild river? This last one is not a value high on the list to most Chinese, but important to global environmentalist viewpoints.

Impacts on Nu biodiversity? Most of this would result from turning a river into reservoirs with consequent impacts on aquatic species, but no one knows the details. Without access to government studies, no one can assess impacts, or evaluate the quality of the studies themselves.

And what about impacts downstream? On the river in Myanmar? The impacts of selling most of the power to Thailand? Vietnam? Or moving it east to southern China’s industrial zones? How about the impacts of transmission lines wherever power does go?

Then there are the impacts of hydropower reducing Chinas’ carbon footprint by helping China use less coal. The list goes on.

As the world’s ‘third pole’, Tibet supplies much of Asia with vital freshwater – what does the future hold for these rivers as things stand now?

Grumbine: As things stand now, no problem. But, the future looks pretty grim.

Despite regional differences across the Third Pole, many Chinese glaciers are losing mass – melting – and this trend is clear into the future. Much argument is about when, not if ice loss in China alone reaches critical thresholds. Projections vary: 2040, 2050, 2060, 2080?

We don’t know, but the loss continues and will continue even if the world begins to deal with carbon emissions— and so far the world has not done so much here.

So this means that there will be less water coming from Tibet’s rivers and that the loss will increase over time. There will be less for people to use and less for all other species to use as well.

What, if anything, can be done to protect the future of these rivers?

Grumbine: Improve sharing of information between countries on transboundary river flows and related issues, creating water sharing management agreements between countries in the region, listen to the experiences of local peoples with how they manage water under conditions of scarcity. Fund water-saving and conservation in urban areas and irrigation systems in rural areas.

Price water at its true delivery cost – done nowhere in China, as water is subsidized by the state.

These measures would begin to help.