The following piece is an excerpt from an article written by Alison Beard for the May 2011 edition of Harvard Business Review.

———-

FORCED TO SHUT DOWN: What a Chinese travel entrepreneur learned from the SARS crisis and its aftermath

The first defining moment of Zhang Mei’s career came in late 1999, when she quit her lucrative consulting job to launch a small travel company in her native China. In December, the Harvard MBA was wearing business suits to New York boardroom meetings; by July, she was in jeans, on the floor of her tiny Beijing office, untangling telephone wires.

The second—and more important—turning point came nearly four years later, when the SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) outbreak hit Asia, battering a travel industry still recovering from the 9/11 terrorist attacks and all but killing Zhang’s fledgling business. Nothing in her training had taught her how to handle the crisis. But she managed to keep the company going, and today AsiaTravel is a leader in its field.

Looking back, Zhang sees that her first big move turned her into an entrepreneur. But it was the SARS experience that taught her how to be a CEO.

“I had high hopes for the business,” she recalls, “and early on I wondered: Am I a good manager? Am I a smart leader?”

After 2003, however, she was battle tested: “These extraordinary events happen once in a decade, and I’m lucky I got mine early.”

A New Direction

Zhang grew up in Dali in China’s Yunnan province, studying English at the insistence of her father, an electrician who’d never attended high school She went to Yunnan University and then worked as a translator, until a Thai banker she had met at a business event encouraged her to apply to Harvard’s MBA program – and promised to pay her tuition if she would join his company after graduation. Once enrolled, she set her sights on a corporate career – “doing the job while other people took care of the details” – and was thrilled to land at McKinsey, a position that required extensive travel and allowed her to repay the banker rather than work for him.

But consulting left her unfulfilled. She wanted more freedom and even more travel. She also wanted to do something good for China. McKinsey gave her a pro bono assignment: strategizing on economic development and conservation in Yunnan province on behalf of the Nature Conservancy, a U.S.-based NGO. Zhang liked nonprofit work but didn’t want to make a career of it. Instead, she came up with a business idea: Launch a travel company to offer sustainable, socially responsible tours of Chinese destinations and communities.

She did a test run, guiding two Nature Conservancy executives and two Washington Post journalists into Tibet – impressing one of them so much that he soon married her. And then Zhang made her move, relocating to Shanghai and taking a job at travel website Ctrip to learn the industry while honing her business plan. A few months later, armed with her own savings and small investments from friends and family, she joined her new husband in Beijing and launched AsiaTravel.

“I had no idea what I was doing, and I never perceived myself as a salesperson, but I became really good at selling my idea – to investors, staff, clients,” she says. “I didn’t even mind all the mundane details of entrepreneurship at the beginning – moving the table and buying the trash can. I just had a conviction.”

With a small, young, enthusiastic staff, a growing list of mainly American clients, and tours focused on everything from city hopping to bird-watching, the company turned a profit in its first year. Then came the travel standstill following 9/11. “She was definitely thinking the business might be finished: good idea, bad timing,” recalls Zhang’s husband, John Pomfret. But the slowdown ultimately served as an impetus to improve her strategy. “Our business had been focused on U.S. travelers, and that was the first time we started thinking about selling in other markets as well,” says Guido Meyerhans, a McKinsey colleague who had invested in AsiaTravel. By early 2002, bookings were back on track. Still, the experience didn’t fully prepare Zhang for the next, more painful crisis.

Second Shock

The first reports of a deadly SARS outbreak in China’s Guangdong province, about 1,400 miles south of Beijing, emerged in February 2003. In March, the World Health Organization issued a global alert, and foreign countries started to release travel warnings for China. But in part because Chinese officials were claiming to have the situation under control, Zhang and her employees carried on as usual. “It was peak season, clients were still coming, and the news was all about how limited the SARS cases were,” she recalls. “So we didn’t make any contingency plans.”

By April, however, cancellations were pouring in, and, late that month, Beijing was declared a danger zone. Zhang thought she could finish up the tours in progress and then redirect her staff to planning and training until bookings resumed. “Then one day,” she recalls, “the contractors renovating our office said, ‘We can’t come in.’” They didn’t want to risk infection by riding the bus. “That’s when it dawned on me: This is serious.”

Belatedly, Zhang and her COO, Jim Stent, started to consider the threat to their own employees, to cancel all trips already under way, and to develop models of what a pandemic might do to their balance sheet. Staff salaries were low by Western standards but could still have eaten up the company’s reserves within six months in the absence of new revenue. Zhang wanted to buy herself at least a year, so she opted for drastic measures: AsiaTravel would cease operations immediately. Both she and the COO would suspend their incomes indefinitely. The dozen or so other employees were asked to forgo 75% of their income until the fall, essentially taking vacation at 25% pay. Once the company reopened, if it did, everyone would be fully reimbursed. They all agreed.

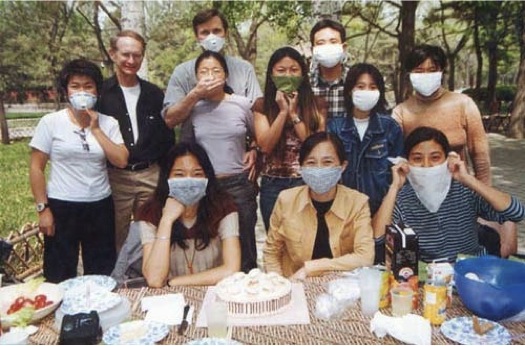

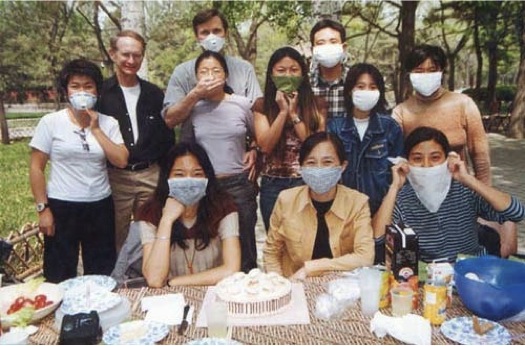

Jia Liming, Zhang’s first hire at AsiaTravel, remembers ending the long- planned bird-watching trip she’d been guiding a week early and then attending an employee farewell party—held at a Beijing park since the SARS threat was considered to be less severe outside. “We thought it was over,” she says.

For her part, Zhang remained calm. But “it was hard to stomach,” she says. “The city was in lockdown, and it seemed like the whole world was coming to an end. Still, I’d been through 9/11, so I was confident we could come back.”

Indeed, by midsummer, following more than 8,000 cases of infection and nearly 800 deaths, SARS seemed to have been contained, and bookings began to pick up again. Zhang and Stent decided to reopen much earlier than they’d expected, on August 1, and called back all the staff.

But it wasn’t as easy as that. Zhang’s top performer in terms of sales and customer service—a young woman she’d hired in 2001 and come to view as a protégé—refused. “She said she wanted more time to hike around another moun- tain,” Zhang says. “I said no. I’d promised a client a proposal by August 5. Two weeks later, she didn’t show. Eventually she came back, all smiles, and I had to tell her I’d given her position away.”

The woman soon launched a regional competitor to AsiaTravel, and over the next few months several other employees left because they missed traveling independently. “It was disappointing because she’d paid these people well and given them opportunities,” Pomfret says.

The next few months at AsiaTravel were nose to the grindstone—reaching out to new clients in the corporate and education sectors; selling, planning, and executing trips; recruiting and training new employees; and replenishing the reserves to pay employees’ back salaries and fund growth. “We had to hustle,” Zhang says. But it paid off. “2004 was one of the best years we’ve had, in terms of profits and new projects.”

Seasoned Traveler

Today, “a little bit older, a little bit wiser”—and having stepped down as CEO in late 2004 to follow Pomfret to the United States, where he had a new job—Zhang points to a few ways in which the SARS crisis helped her become a better leader.

First, it taught her the importance of scenario planning and proactive communication with staff and customers in crisis situations. “I was responsive to client questions during SARS,” she says, “but I didn’t take action until May, by which point I was a little bit cornered.” Since then, AsiaTravel has established crisis response guidelines. “Number one is to make a judgment call as early as possible,” says Zhang, who remains chairwoman and part owner and oversees market- ing from her suburban Maryland office.

When riots broke out in Tibet during the 2008 Beijing Olympics, for example, the company issued a press release and sent instructions to staff and guides the next day. Meyerhans notes that employees are also in closer contact with provincial government officials to ensure access to the most accurate information. “Once you start preempting clients’ questions, they feel you’re in control,” Zhang explains.

The employee fallout from SARS was also educational. When people Zhang had trusted left her, she realized she needed to think harder about whom she was recruiting and why. In the first years of AsiaTravel, she explains, “I was looking for the passionate, free-spirited traveler I should have been looking for the customer service, travel industry professional—someone who really gets satisfaction out of serving other people.” She was also giving promotions and pay raises too quickly, on an ad hoc basis, without establishing benchmarks for advancement, including long-term commitment to the company.

After SARS, Zhang built a different kind of team, including more-seasoned managers who could handle day-to-day operations when she left in 2004. “One of her biggest achievements,” Meyerhans says, “was making that transition so smoothly, based on the trust she had in the employees she’d hired.”

More broadly, he thinks the two early hits of 9/11 and SARS forced Zhang to be a more creative, confident executive, diversifying and expanding the company each time. “We had high-net-worth individuals and small groups, but that’s a difficult business to control and grow, so we started to build up the corporate and the educational business,” in addition to targeting different geographic regions, he explains. And Zhang has insisted in the years since that AsiaTravel stick to that forward-thinking strategy. During the recent financial crisis, for example, even as competitors retrenched, “I doubled down,” she says. “I plowed more than 50% of our profits into marketing and IT. I knew that China’s rise, and its tourism and our business, would outlast the recession.”

One last benefit of enduring the SARS period, with no income, was that it reinforced Zhang’s passion for her venture. “You go through self-doubt moments,” she recalls. “When the profits aren’t great, you say, ‘Wow, how did I labor another year with no payback?’ But I’m in this be- cause I enjoy it. As long as I have a comfort level that reaches the minimum threshold, I can seek satisfaction.